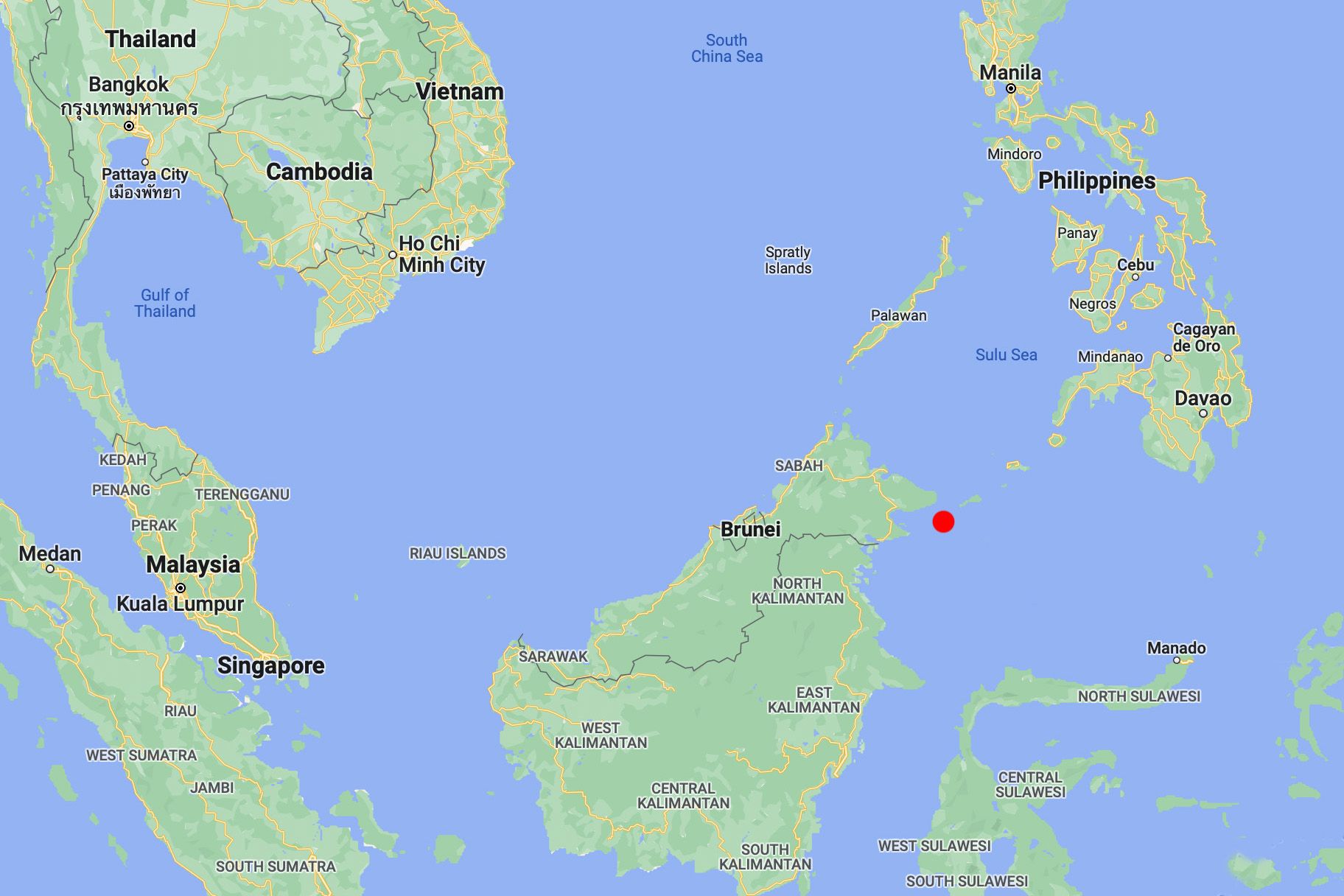

Suang Pukul is populated by Badjao and Sama tribesmen, like scores of similar sea villages strewn across the Sulu Sea, from Brunei and Sabah on Borneo island all the way to Mindanao. Fiercely independent and equally iconoclastic, they are the proud remnants of the 500-year-old Sultanate of Sulu, an aquatic empire that eluded the control of a succession of colonial powers, including the Spanish and Americans. Modern buccaneers, they recognize no borders and no rule but that of the open sea, as they smuggle goods and guns across pirate-infested waters that form a sort of Silk Road of the Sea.

Theirs is a real-life Waterworld, from birth to death. Many children in Suang Pukul have never walked upon land. Instead, they make playgrounds among the tangle of wood-slat bridges that run helter skelter through the ramshackle communities miles from Sitangkai, the nearest landfall. Not that it’s a deprived existence. Instead of wagons or bicycles, toddlers receive tiny rough-hewn canoes as presents. Water volleyball and piggy-back water wrestling games are their sports. And, just when I think I have finally found the sole site in the Philippines without a basketball court, on a motorboat tour of some nearby sea villages, over a rickety wooden deck, I spy a rusty metal hoop.

Reaching the remote sea villages isn’t an easy. Filipino officials warn away foreigners, and passports are demanded at departure points in Zamboanga, even though the islands are, legally anyway, part of the Philippines. It’s a frightening reminder that government control has never reached these untamed isles. Kidnappings are commonplace and insurrection is a cherished tradition. Despite a much-heralded truce signed this year with Muslim rebels, Sulu was the scene of fierce fighting just two months ago.

Guns are far more prevalent than beach gear as we island-hop down the string of 500 islands in the Sulu Sea. Yet, even without the all-night "Jingle Bells" serenade, the welcome is quite uplifting when we abruptly hop off a rented motorboat and announce, by way of presents and hand gestures, our intention to spend a few days amongst these rugged sea gypsies.

Still, Christmas preparations don’t amount to much amongst these devout Muslims. For stocking stuffers, there is little more than dried fish, a few rounds of ammunition and the occasional stick of dynamite.

All are readily available in Sitangkai, a town of about 10,000 people, where dynamite sells for about US$1.20 a stick, according to a Julbaya Parangsaya. "Of course, you must know where to go," he says, then sheepishly adds in a whisper: "We can take you if you want some, but it is ee-legal."

Sitangkai is hardly a city in any conventional sense. Local ferries dock a mile or so away at a floating wharf. Access is impossible across the shallow reef except by smaller boats. Cruising main street is remarkable. You do that by boat and the local teens hang out on a series of overhead bridges. Hollywood wasted well over US$100 million on the sets of "Waterworld," which could have been filmed with stark realism in Sitangkai.

There are no streets, only miles of wooden walkways that connect the city’s hundreds of stilt houses. There are mosques, schools, even an entire open-air food market, all perched over water.

Sitangkai does connect to a small island, but that’s deserted except for a series of cemeteries that display the multi-ethnic nature of the seafarers who passed this way. Besides Muslim and Chinese decorations, there are also totems, stick figures and small wooden ships, offerings to the animistic spirits who still linger.

But people? No way. "The island is for the dead," explains Hadji Yusof Abdulganih, who runs a one-room guesthouse for the dozen or so foreigners who slip into Sitangkai each year. "Around here, only the dead live on land."

Words by Ron Gluckman

©2022 All rights reserved.