to be an American

by Stuart Isett

Above: Many Uch walks past a mural painted on a Cambodian grocery store in White Center, Washington

Congratulations to my old friend Many (“Mah-nee”) Uch, who finally obtained his US citizenship last week. Sadly, I could not be there to celebrate with him in-person and due to COVID, it was not a public event. The last photo below was taken a week ago, celebrating with him over a beer in Seattle - Many, always with a smile. The other images were taken from 2006 onwards, when I first met him and started following his fight for justice.

If you don’t know Many’s story, he was born in 1976 in Battambang, Cambodia, under the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. His mother fled to Thailand after the regime fell, leaving Many’s father behind, and after 4 years in a Thai refugee camp, the family eventually moved to the US in 1984 and settled in White Center, just south of Seattle. Many's family were farmers back in Cambodia, arrived with nothing and lived in poverty, traumatized by a war and genocide the US government had a direct role in starting.

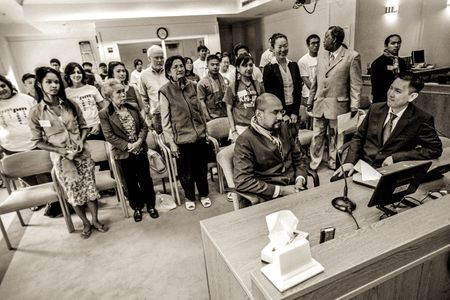

Like many of his peers struggling to adapt to life in America, after years of violence, trauma and struggle, Many made mistakes. After an arrest and three year prison sentence for first-degree robbery in 1994, he languished in immigration custody for an additional two and a half years awaiting deportation. He was eventually freed thanks to a 2001 Supreme Court ruling banning indefinite detention but was still under orders for deportation back to Cambodia, away from his family, wife and US-born children. Nearly a thousand Cambodian-Americans have been deported since the mid-2000s, re-traumatizing many of these refugees. At least 2,000 more in the US still face deportation.

Many is just one piece of a larger story I have worked on since the early 1990s on young Cambodian refugees, now middle age men, many of whom have either been deported or are still facing deportation; punished twice for acts often committed 20 or more years ago for which they already served time. Many stood up, though, and fought for his rights. First obtaining a pardon from Washington Governor Christine Gregoire in 2009 and then starting the long and arduous process for obtaining citizenship.

Today, hundreds of Cambodian refugees still face deportation, even though President Biden has put them on hold for now. Many told me last week he suffers from “survivor’s guilt” having seen the tears of so many families that have been shredded by these policies. Having spent time with the deportees back in Cambodia, it pains me to know that even in a moment of happiness, my friend's struggles continue as he sees this continuing trauma inflicted on his community.