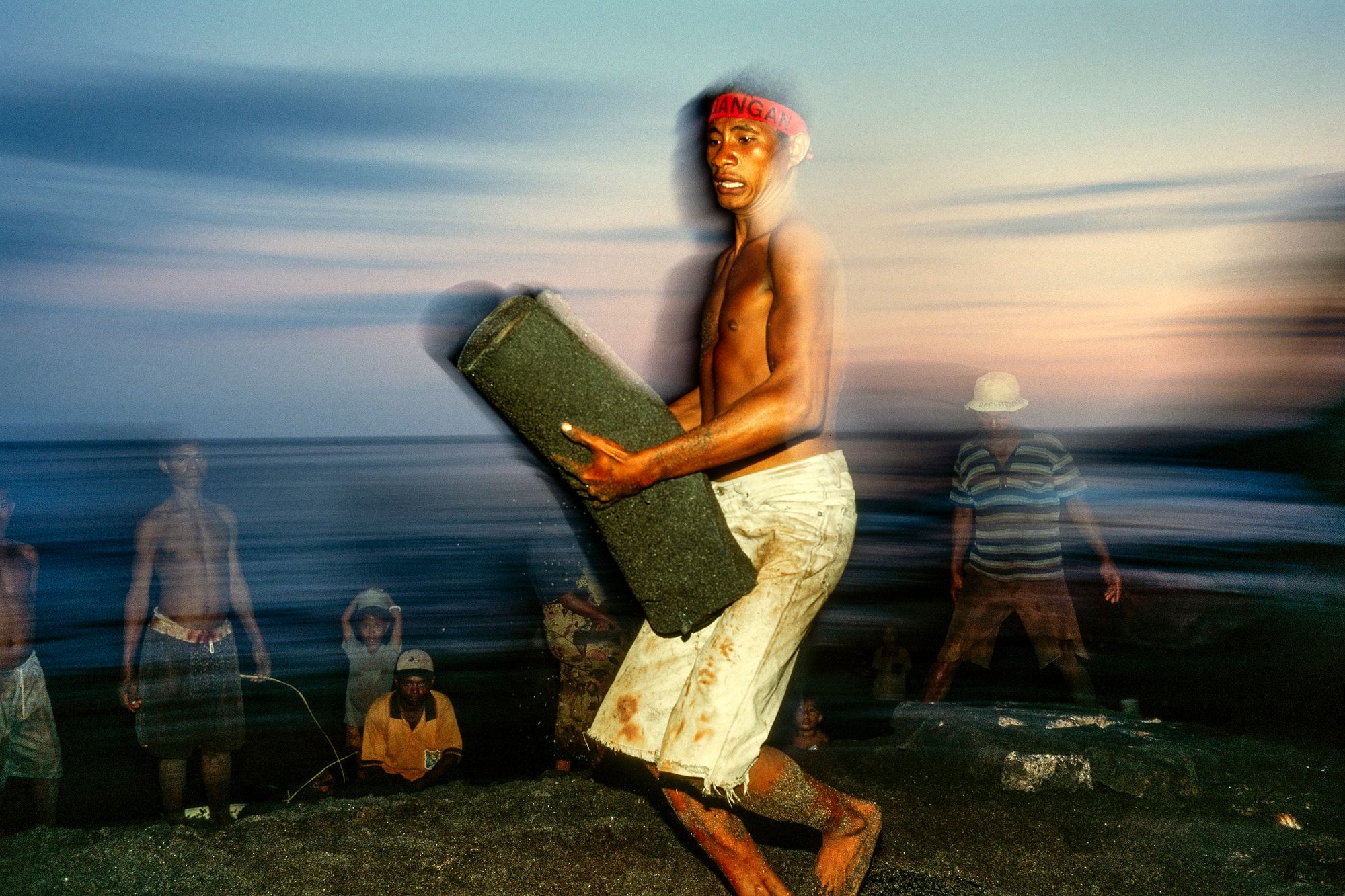

AUGUST, 1999 - Lamalera, Indonesia is one of the last places on earth where traditional whale hunts exist. The men of the village take to the sea in 12-metre-long wood boats powered by oars and reed sails, carrying bamboo harpoons fashioned with locally made steel tips. The villagers also hunt other marine life, with pilot whales, manta rays and dolphins being the most common catch When I arrived by boat to the tiny island in August, 1999 and waded ashore with my camera over my head, I knew the odds were long I would actually document a whale kill. The villagers typically capture a whale a month during the May until October whaling season but somehow on my first day out to sea in the ‘Teti Heri’, along with 6 other boats, the hunters managed to catch a 14 meter long sperm whale. Killing a whale takes years of experience. The lama-fa (harpooner) job is inherited, passed from father to son. The role warrants a unique position in Lamaleran society on account of its danger and the precise skill required. The lamafar must strike a main artery running down the whale's back; a little bit off the mark and instead of a fatally wounded whale, the villagers will have an angry and powerful beast on their hands. Boats have been dragged as far as East Timor by wounded whales and, over the years, whalers have lost life and limb during the hunts.

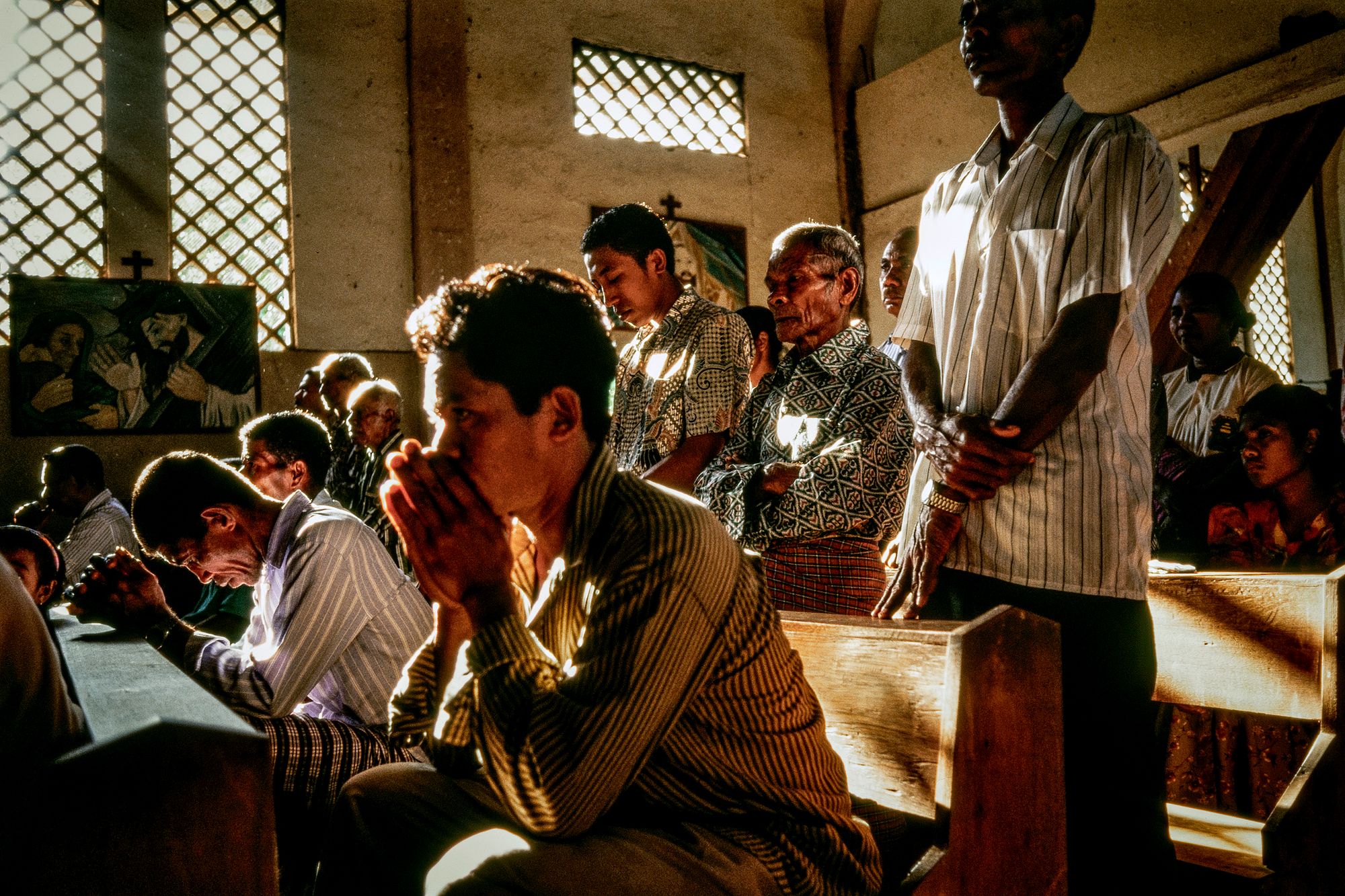

One whale can feed the entire village of 2,000 for over a month and extra meat is dried and bartered for rice and corn on nearby islands. Butchering the whale will take over 30 people a day and the meat is divided up according to traditional communal rules. Meat around the eyes always and the penis go to the lamafar and choice cuts are also given to the owners of the boat involved in the kill. Other boats get a share according to how they much helped. The hunting of marine mammals by communities which have historically been dependent upon eating whale meat is known as Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) and the IWC recognises the rights of certain peoples to hunt whales not for profit but to fulfil nutritional and cultural needs.

All these images were shot on Fuji Provia 100 slide film, a real challenge in the bright sunlight, bouncing around on the ocean, with limited frames. It's the kind of story I wish I had the fast, high resolution digital cameras I use today! But I do believe the scarcity and technical limitations of film made you a better photographer. Make every frame count and understand the light with precision.