I started my Cobain trip at the Marco Polo, a no-frills motel on the gritty periphery of Seattle that Cobain frequented in his final days, when his heroin addiction controlled his life. According to the 2007 BBC documentary “The Last 48 Hours of Kurt Cobain,” Cobain used to duck out of his mansion in the exclusive Denny-Blaine neighborhood to meet one of his preferred heroin dealers along Aurora Avenue. He would then retreat to room 226 of the Marco Polo to shoot up.

The reception area was closed when I arrived late on a Monday night in February, so I rang the doorbell. Moments later, a small sliding window opened, and a man named Jonathan popped his head out. He sized me up wordlessly, slid the window shut, and re-emerged moments later in the reception area, wearing an undershirt, a pair of boxer shorts and woolly socks.

“This place was the Wild West back when Kurt stayed here,” he said, checking me into Cobain’s favorite room as a TV blared from his living quarters behind the reception desk. “We had hookers throwing TVs out the windows here, drug dealers, junkies, you name it.”

Having worked there for many years, but not back then, he suggested that the neighborhood had improved since Cobain frequented the place, but my room was a grim time warp. There were hairs on the pillows, splotchy stains on the sheets that could have predated Nirvana, and scratchy bath towels.

Before buying the expansive home at 171 Lake Washington Boulevard where he was found dead, Cobain and his wife, Courtney Love, lived in a variety of high-end Seattle hotels, including the Inn at the Market, the Sorrento Hotel and the Four Seasons Olympic, now the Fairmont Olympic. The Fairmont and the other luxury hotels Cobain lived at don’t advertise the connection, but the arty Hotel Max embraces Seattle’s grunge connection with a “Sub Pop” floor devoted to the local indie record label that discovered Nirvana.

Cobain is often linked to Seattle, but he spent less than two years living in the city. He lived in more than a half-dozen homes, and slept in countless other places in Aberdeen and the neighboring towns of Montesano and Hoquiam, and wrote many of Nirvana’s best-known songs in Olympia before moving to Seattle in 1992. I started my Cobain homes tour in Montesano, a small town where members of the influential punk band the Melvins grew up.

Standing outside 413 Fleet Street South, the home that Cobain lived in with his father from late 1978 to March 1982, was a neighbor named John Bell, who told me that when Cobain’s mom used to visit him, he could hear them yelling at each other from across the street. Fleet Street was a step up for Cobain, but Mr. Bell said that the modest, century-old house with red vinyl siding and newspapers covering the windows seemed mostly empty.

A few minutes outside Montesano, I drove into the Country Estates mobile home park, where Cobain lived with his paternal grandfather, Leland Cobain, after leaving Fleet Street. While parked next to a speed limit sign that warned, “Violators will be Prosecuted, Survivors will be Shot,” a man named Jerry who was out for a walk offered to introduce me to Gary Cobain, Leland’s son and Kurt’s uncle.

“My dad greeted Nirvana fans from all over the world here,” said Gary Cobain, who moved into the mobile home after his father died last May. “It kept him busy.”

Shadowing the Chehalis River, I drove west along Olympic Highway to Aberdeen, an old logging city once called “the roughest town west of the Mississippi.” Before a tableau of billowing smokestacks there is a sign, erected by the Kurt Cobain Memorial Foundation in 2005, that reads: “Welcome to Aberdeen, Come As You Are,” a reference to one of Nirvana’s hit singles and now the unofficial motto of the city.

The mayor of Aberdeen, Bill Simpson, had offered to take me on a mini-Nirvana tour but the receptionist at city hall said he was helping to negotiate a standoff.

“There’s some crazy guy holed up in his attic who fired some shots out the window and was making threats,” she explained.

Before I could tell her not to bother the mayor, she had already spoken to him, and minutes later he bounded into the room. “Kurt went to Seattle and became famous, but he was from Aberdeen,” the mayor told me as we piled into his Chrysler minivan. “Seattle embraced him as one of their own, but then he killed himself, and suddenly he became an Aberdeen guy again. We’re happy to reclaim him.”

A chair in the 1210 East First Street home.

We drove by 1210 East First Street to have a look at the home where Cobain lived for several years as a child in the city’s notorious “Felony Flats” neighborhood, which is rife with boarded-up homes. His mother, Wendy O’Connor, who now lives in California, placed the four-bedroom modest home, assessed at $67,000, up for sale in September at $500,000. Jaime Dunkle, a Nirvana fan in Portland, Ore., is raising money to turn the place into a museum, so it “doesn’t end up in the clutches of capitalist greed,” as she put it on her website.

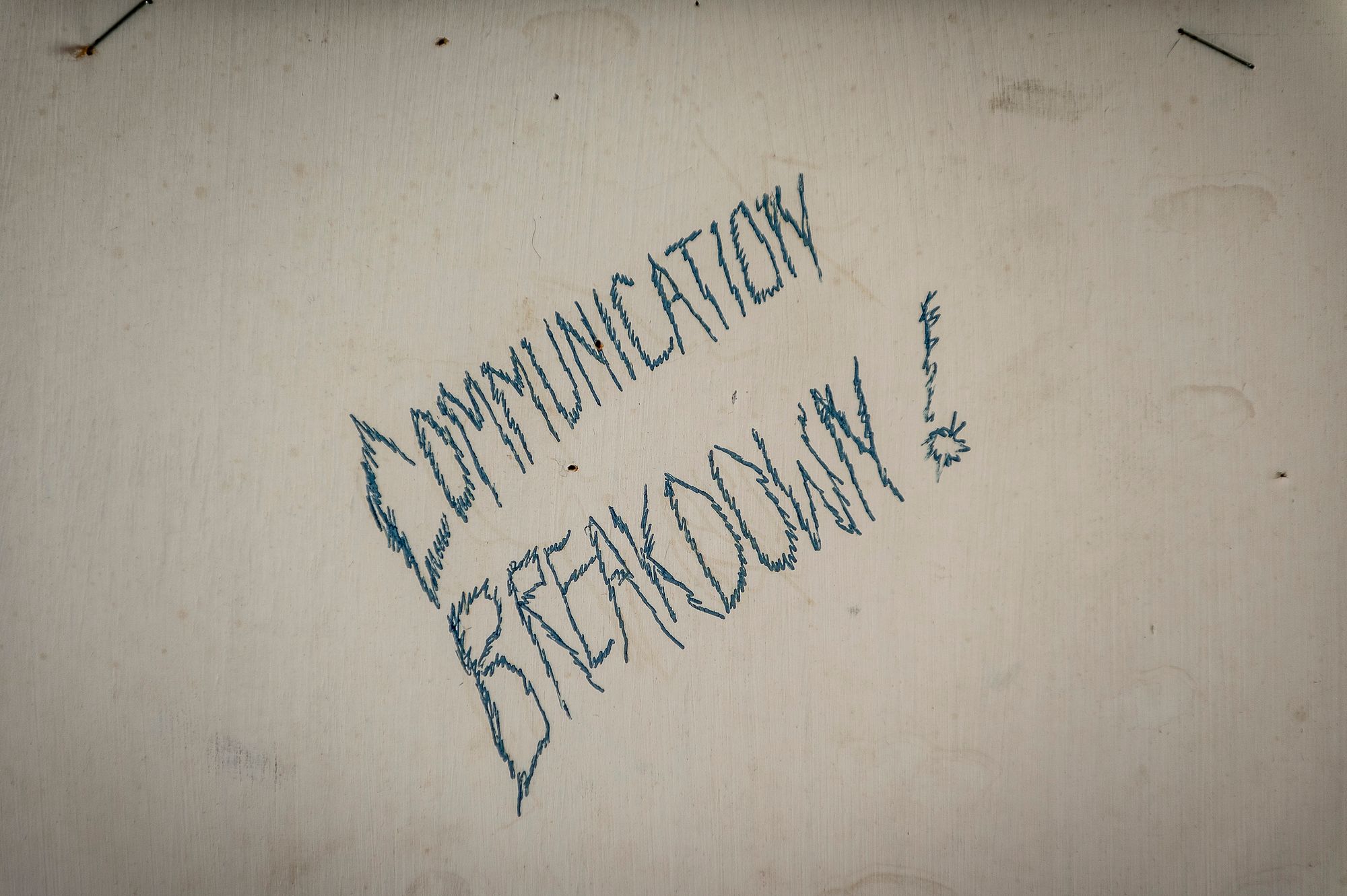

A real estate agent gave me a tour of the home, which is being marketed as a “once in a lifetime opportunity to own a piece of rock history.” It was like a stroll into a 1970s time warp. The vintage kitchen featured orange, black and gold carpeting, the hallway had wood shingles, and Cobain’s bedroom was just as he left it: with a hole punched in the wall and plenty of graffiti paying homage to bands he liked (Led Zeppelin, Iron Maiden) and perhaps his favorite beer, Olde English 800.

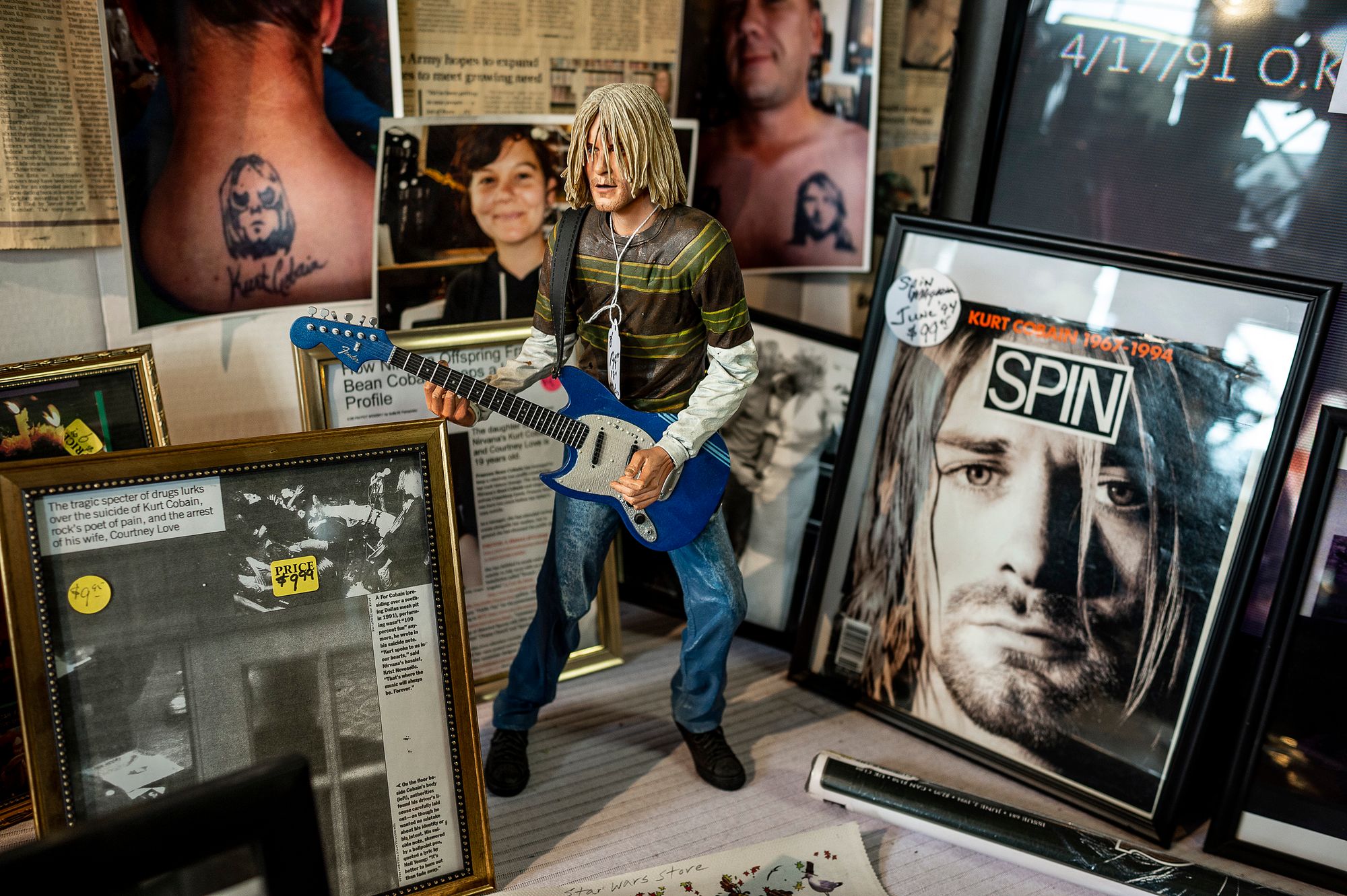

A former manager of the men’s shoe department of Aberdeen’s J. C. Penney store, Mr. Simpson, 73, isn’t in the heart of the Nirvana fan demographic. But when I dialed up “Territorial Pissings,” the most aggressively punk Nirvana tunes I could find on my iPhone, he insisted that he liked it. While we were checking out the recently unveiled and much maligned Kurt Cobain statue, a not-very-flattering rendition of Cobain in ripped jeans with a tear falling from one eye, at the Aberdeen History Museum, Mr. Simpson took a call and relayed the news that the standoff was over. “Good news, the guy surrendered,” he said.

Aberdeen’s must-see Cobain site is a small park, opened in 2011 by the Kurt Cobain Memorial Foundation, called Kurt Cobain Landing, which sits at the foot of the Young Street Bridge, the inspiration for the song “Something in the Way.” Cobain claimed that he lived under the bridge for a time, and while most who knew him don’t think he did, it was clearly one of his preferred hangouts. Set along the banks of the murky Wishkah River, the strangely appealing little park features a guitar sculpture, a likeness of Cobain with the lyrics to “Something in the Way,” a headstone with some amusing Cobain quotes (sample: “I’m a walking bacterial infection”), a Kurt Cobain “air guitar” sculpture and a collage of Nirvana-related graffiti under the bridge itself.

After the tour, I checked out a host of Nirvana-related sites, including six different homes where he once lived.

I knew that Cobain had grown up poor, but seeing all of the places where he lived, including Dale Crover’s porch, at 609 West Second Street, where he slept inside a refrigerator box for a time, gave me a new appreciation for how much he overcame.

Surely no one who knew Kurt Cobain then could have predicted that someday he’d have two towns fighting to claim him as a native son.

Hoquiam, Aberdeen’s neighbor and rival, issued a proclamation honoring Nirvana in February, prompting Aberdeen to “reclaim” Kurt with a Cobain day of its own. The home where he lived in Hoquiam from birth until he was 2 looked just as forlorn as most of his residences in Aberdeen but Hoquiam also had an appealing, if dated, little downtown.

Two months after playing their first ever gig, at a house party in Raymond, Cobain left Aberdeen and moved to Olympia, a comparatively bohemian oasis where he found his creative muse. My first stop was 114 Pear Street, a small house in central Olympia split into three apartments where Cobain lived with Tracy Marander, his girlfriend at the time. She supported him while he wrote many of the songs that would appear on “Nevermind.” They broke up, but he kept their tiny apartment until July 1991, when he returned from doing promotional work in Los Angeles for the forthcoming “Nevermind” to find that he’d been evicted, his belongings discarded in the street like trash.

Scott Taylor, the lead singer and guitar player for the Hard Way, lives in apartment No. 3, where Cobain wrote Nirvana’s most recognizable songs, and he offered me a tour. Inside the compact one-bedroom apartment, Mr. Taylor has a Nirvana poster featuring a photo of Cobain posing in what is now Mr. Taylor’s backyard, and another photo of the band playing an early gig. The fact that a musician is bathing in the same black claw-foot tub Cobain used to pass out in isn’t a huge coincidence: For a small city, Olympia’s music scene is as vibrant as they come.

At the old-school McMenamin’s Spar Café, where he reportedly liked to hang out, I asked my waitress, Heidi, about Cobain’s connection to Olympia.

“Kurt lived at the house I live in now,” she said. “He lived everywhere, but got kicked out of each place.”

On my way back up to Seattle, Nirvana tunes rattling my rented Corolla, I felt that trying to follow in Cobain’s footsteps was a lot like chasing a shadow. That was nowhere more so than in Seattle itself, which has changed almost beyond recognition since he died.

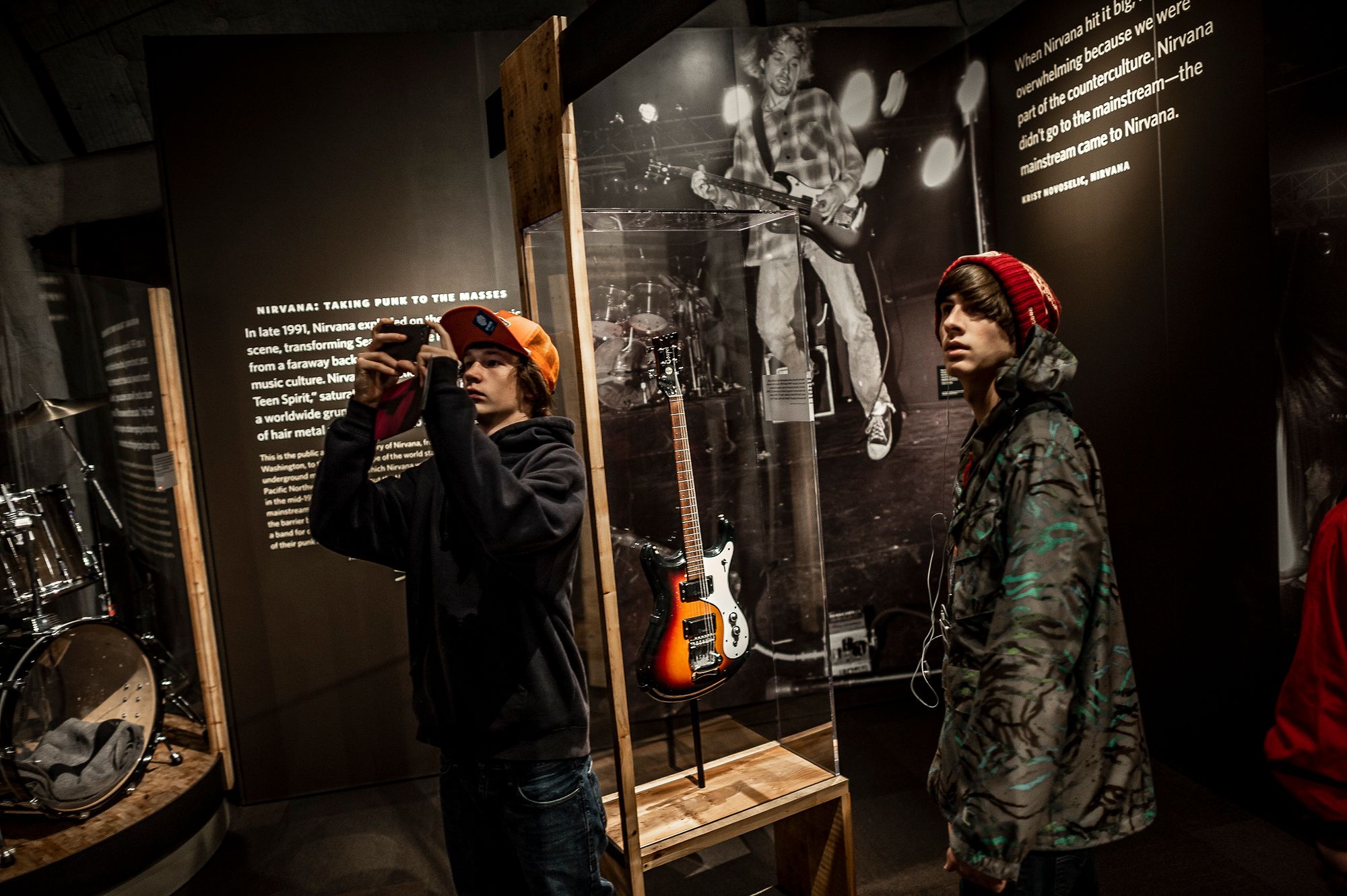

Bruce Pavitt, the founder of the Sub Pop record label, which signed Nirvana, and the author of “Experiencing Nirvana: Grunge in Europe 1989,” told me that the one Seattle venue where Nirvana played that has largely stayed the same is the Central Saloon, the city’s oldest bar, established in 1892. Most rock historians consider a show Nirvana played at the Vogue, now a hair salon, the band’s first Seattle gig, but Mr. Pavitt insisted that a Nirvana showcase he attended on April 10, 1988, at the Central Saloon was the band’s very first.

“No one else remembers it,” he said, “because it was just me, the doorman and about three other people.”

The Central is still a grand old tavern, but when I visited it in late February, it was filled with a well-dressed, affluent crowd. Other notable Nirvana venues in Seattle include the Crocodile, a once grungy club that has now been renovated, the OK Hotel, where the band first played “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” now an upscale condo, and Beehive Records, where Nirvana played a legendary in-store concert just before the release of “Nevermind”; it is now a Petco store. Linda’s Tavern, a celebrated neighborhood bar nicknamed the “grunge Cheers” was where Cobain was last seen alive.

Tiny Viretta Park, adjacent to the imposing estate on Lake Washington Boulevard that Cobain and Ms. Love moved into less than four months before his death, along with their daughter, Frances Bean Cobain, also has endured. Nirvana fans from around the world come to etch graffiti in the park’s lone bench or leave flowers, even though the city of Seattle has refused to rename the place Kurt Cobain Park.

Walking around the Denny-Blaine neighborhood, the last place where Cobain lived, I felt that Aberdeen’s most famous son never really fit in with Seattle anyway, certainly not in this exclusive area. I sat on the unofficial Cobain bench and thought about how the Cobain haunts in Seattle, Olympia and Aberdeen mirrored the big picture of what’s happened to these places. Olympia is artier than it used to be, with struggling musicians everywhere, even in Cobain’s old apartment. The dilapidated Cobain childhood homes in Aberdeen spoke to the depressing reality that many young people there are still trying to escape, perhaps now even more than before. The fact that most of the grungy places where Nirvana played in Seattle are either gone or completely different is a testament to the continued gentrification of the city.

As these thoughts swirled in my head, the words to a song I had heard during an open mike at Tugboat Annies in Olympia the night before popped into my head.

A diminutive, bearded rapper named MC Swamptiger played “Peace,” a song whose final lines, sung — no, screamed — with conviction made me think of Cobain: “IN MY DEATH, I FINALLY FOUND MY PEACE! IN MY DEATH, I FINALLY FOUND MY PEACE. I SAID, IN MY DEATH, I FINALLY FOUND MY PEACE!”

Words ©2022 Dave Seminara

Originally published in 2014 in The New York Times